What can you tell youth about an increasingly dystopic future?

As we continue to spiral into environmental chaos and its consequences, what do we tell our children? Are we even talking about this with them? What do you say? Do they listen? Do you have any moral authority to speak from? To be clear, I speak from a life of refusing to own a car. And a life of resistance to fossil fuel pipelines and infrastructure.

Many people today seriously consider not having children.

The increasingly foul air in cities in the 1960s was a warning. And that should not have been ignored. Although introducing catalytic converters in the mid-1970s reduced the visible smog, they didn’t stop the fossil fuel emissions. But did make it easy to ignore the ever-increasing pollution.

Many people now blame the deep deceptions of the fossil fuel industry as an excuse for not having done anything about greenhouse gas emissions. When, in fact, they chose to do nothing that would interfere with the convenience of automobiles.

What cuts me deeply is knowing we absolutely would not be where we are now if we had invested in mass transit and built walkable communities instead of a car culture.

While many of my friends and I have worked hard on racism, war, poverty, and the forced assimilation of Native children, none of those compare to the travesty of what we have done to Mother Earth.

I recently came upon an interesting article by Steve Genco in response to this Reddit post.

I’m a teen and I’m really scared for my future

“I’m so afraid of climate change. I just turned 17 not so long ago and I’m afraid I’ll never get to grow up because of the way our Earth is going.

“Most of my friends and family are apathetic, such as my parents who don’t like me talking about this stuff since they feel we can’t really change anything. My mom thinks it’s completely irreversible. I hate holding it all inside all the time. …

“I guess what I really wanna hear is it’s all gonna be ok even though it’s probably not the truth. I’m just scared. I’d appreciate any positive news or insight from those who feel the same way and how you manage it while doing everything you can. Thanks for reading.”

I’ve been thinking quite a bit about what to say to a teenager like this young person to help them prepare for the dangerous world they are about to inherit. I concluded the best advice I could give would be to suggest some questions they need to consider. So here are four questions I believe any young person who wants to survive the 21st Century needs to ask and answer for themselves:

In Part 1:

- What predictions can you rely on?

- What will give your life meaning?

In Part 2:

- What skills and mental habits will you need?

- How will you live?

What Can You Tell a 17 Year Old Who’s Afraid of Dying from Climate Change? Part 1 by Steve Genco, Aug 29, 2023, Medium

I like the idea of proposing questions for young people to ask themselves, to come to their own understanding, and to be invested in their answers. (Many Quaker meetings use questions, or queries, to guide spiritual discussions).

The article lists the following predictions we can rely on:

- It’s going to get hotter

- The weather is going to get more unpredictable and more extreme

- Natural disasters are going to arrive at greater and greater frequency

- Economic inequality (income and wealth) is going to get worse

- We will continue depleting the natural world

- The effects of climate change will be unevenly distributed around the planet

- We will run out of oil and gas

What will give your life meaning?

This is such an important question. Throughout the coming horrific times, we must focus on what gives our lives meaning. This will allow us to be self-fulfilled no matter what is going on around us. Allows us to search through all the chaos for what gives our lives meaning and to not be led down false paths. We don’t have the time or capacity to do anything but that. No matter what happens, we can build on our own core values.

Fewer and fewer people are engaging with organized religions to find meaning in their lives. Organized religions have been involved in many atrocities.

Organized religion is usually not about spirituality. Spirituality in any of its many forms can give your life meaning. That has been and continues to be true for me as a Quaker. (I don’t think of Quakerism as organized religion). Quaker worship involves gathering together for about an hour each week in silence to seek guidance from what we call the Inner Light, the continued presence of the Spirit today and into the future. Whatever spiritual source you find, I believe that can be tremendously helpful to find a path through what is coming. I would go so far as to say essential.

Psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan began developing what they called Self-Determination Theory (SDT) in the 1970s. SDT emerged out of Deci’s interest in intrinsic motivation.

Deci began searching for the underlying needs that intrinsically motivated behavior seemed to fulfill. He and Ryan discovered three motivators that appeared to represent basic or innate psychological needs.

- A need for autonomy: People need to feel self-directed and in control of our actions. We are more motivated to pursue activities we voluntarily and freely choose for ourselves, as opposed to activities we feel are imposed on us by other people or external circumstances.

- A need for competence: People need to feel accomplished and capable. We are more motivated to pursue activities we feel competent to accomplish. We are also motivated to pursue activities that allow us to increase our competence through practice and repetition.

- A need for belonging: People need to feel connected to others. We are more motivated to pursue activities that make us feel closer to others and that can be pursued in a supportive social context. This need is called relatedness by Deci and Ryan.

Throughout their research, Deci and Ryan studied how the goals people pursue on a daily basis and throughout their lives fulfill basic needs and contribute (or not) to personal wellbeing. In these studies, they found compelling evidence that:

placing strong relative importance on intrinsic aspirations was positively associated with well-being indicators such as self-esteem, self-actualization, and the inverse of depression and anxiety, whereas placing strong relative importance on extrinsic aspirations was negatively related to these well-being indicators.

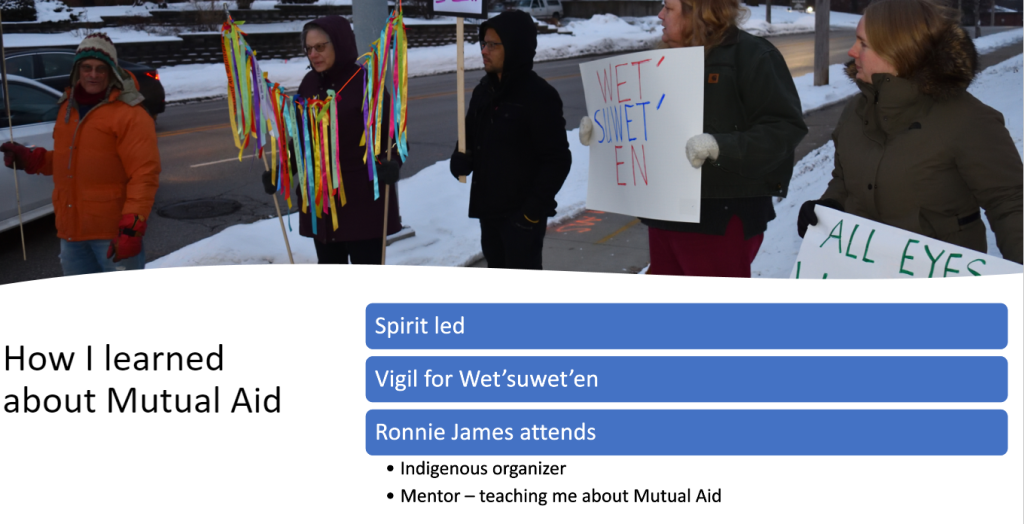

The needs for autonomy, competence, and belonging are exactly what Mutual Aid is about. These are the Points of Unity of my Des Moines Mutual Aid community.

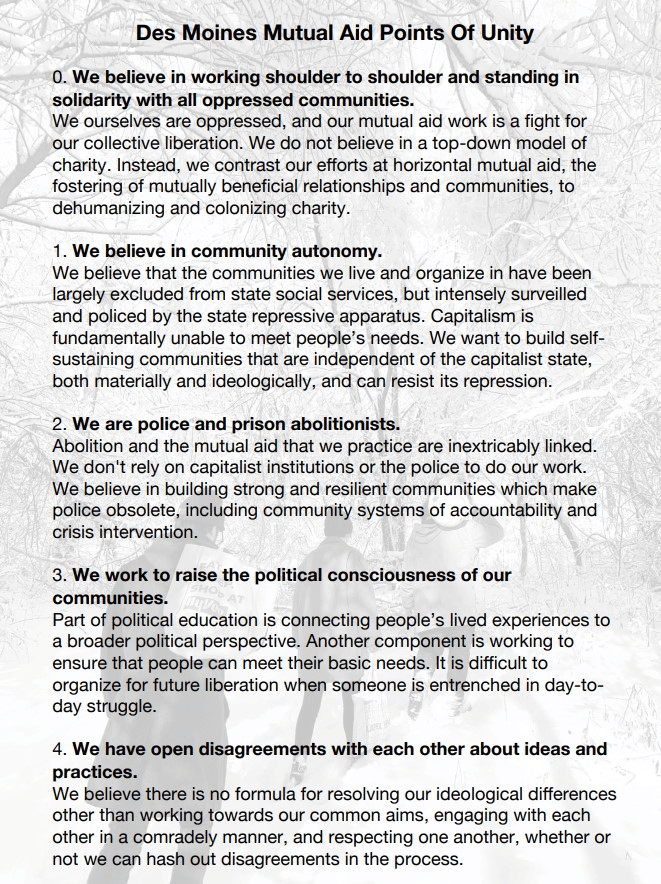

Mutual Aid Points of Unity

We believe in working shoulder to shoulder and standing in solidarity with all oppressed communities

We ourselves are oppressed, and our mutual aid work is a fight for our collective liberation. We do not believe in a top-down model of charity. Instead, we contrast our efforts at horizontal mutual aid, the fostering of mutually beneficial relationships and communities, to dehumanizing and colonizing charity.

We believe in community autonomy.

We believe that the communities we live and organize in have been largely excluded from state social services, but intensely surveilled and policed by the state repressive apparatus. Capitalism is fundamentally unable to meet people’s needs. We want to build self-sustaining communities that are independent of the capitalist state, both materially and ideologically, and can resist its repression.

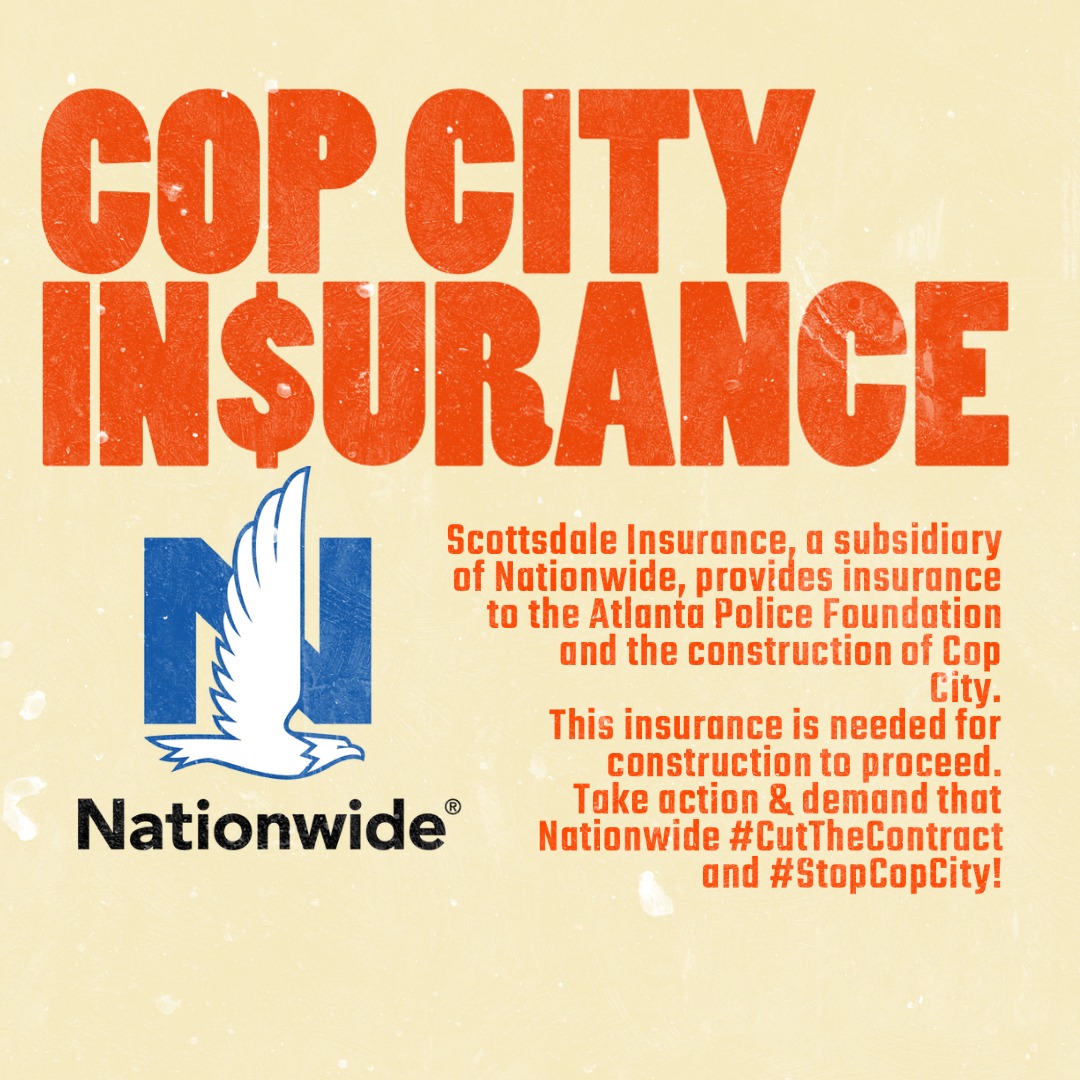

We are police and prison abolitionists.

Abolition and the mutual aid that we practice are inextricably linked. We don’t rely on capitalist institutions or the police to do our work. We believe in building strong and resilient communities which make police obsolete, including community systems of accountability and crisis intervention.

We work to raise the political consciousness of our communities.

Part of political education is connecting people’s lived experiences to a broader political perspective. Another component is working to ensure that people can meet their basic needs. It is difficult to organize for future liberation when someone is entrenched in day-to-day struggle.

We have open disagreements with each other about ideas and practices.

We believe there is no formula for resolving our ideological differences other than working towards our common aims, engaging with each other in a comradely manner, and respecting one another whether or not we can hash out disagreements in the process.