[My foundational stories are related to the intersections between my Quaker faith, protecting Mother Earth, and photography. My faith led me to try to share my spiritual experiences and show my love for the beauty of Mother Earth through photography.]

Yesterday I described where my story related to photography is at this time. Today I write about where I am regarding protecting Mother Earth. The beginning of my stories about protecting Mother Earth and the water can be found here: Foundational stories about care for Mother Earth.

Concern for Mother Earth has been a constant in my life. I was 20 years old when I moved to Indianapolis and was horrified by the thick, noxious exhaust from cars. I couldn’t be part of that and have lived without a car since then (1970).

My foundational stories now

Protecting Mother Earth

It took a while for me to become comfortable with the term Mother Earth. But vocabulary can affect how you feel about something. Having Earth as your Mother describes a living relationship. This is one of the many things I’ve learned from my Indigenous friends.

It is a dichotomy that today, despite knowing the many ways our environment and so many other things are collapsing, I have more hope than I’ve had for years. That’s because of the coalitions of people coming together to heal each other and Mother Earth. We can’t be so paralyzed with fear about what may be coming that we don’t enjoy the beauty all around us.

Following are some ways I’m involved in protecting Mother Earth now.

- Buffalo Rebellion

- Mutual Aid

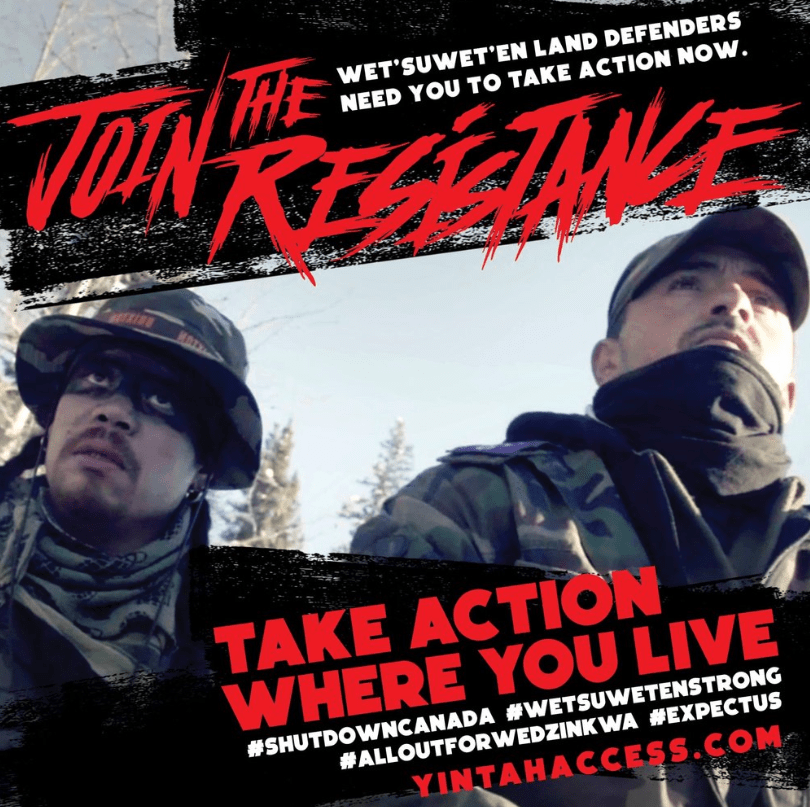

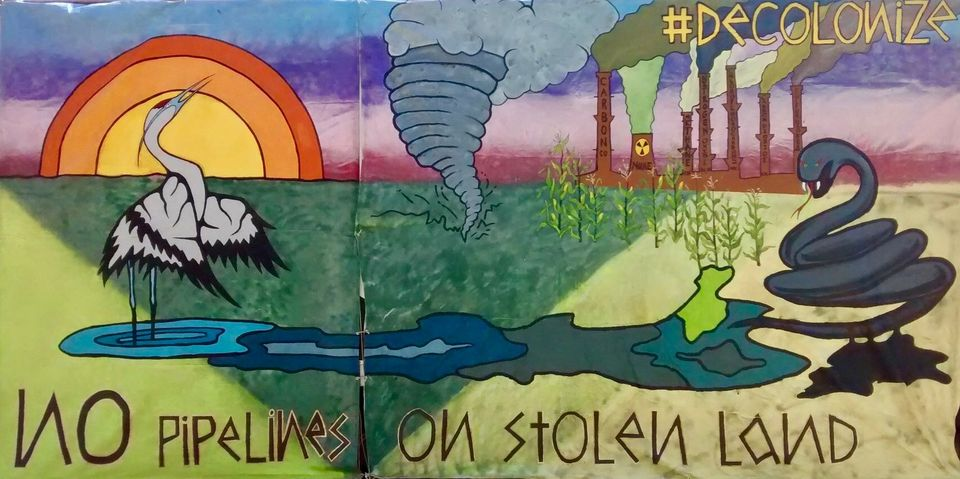

- Wet’suwet’en

- Bear Creek Friends Meeting

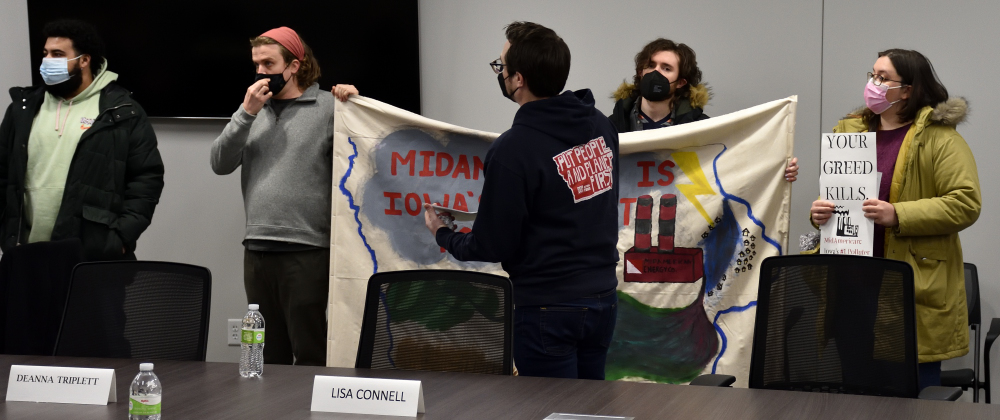

Buffalo Rebellion

Last night I participated in a meeting of the Buffalo Rebellion, which I’m proud to be a part of. This coalition of environmental activists is one of the things that gives me hope. Realizing we are all working on similar things, this coalition is being built to empower our work and support one another. Last night someone remarked that we’ve all suffered trauma and are all in need of healing.

Following is a description of the Buffalo Rebellion, including a link to a recording of my friend Sikowis Nobiss describing it.

The topic this month is on a newly formed Green New Deal coalition in Iowa called Buffalo Rebellion formed to protect the planet by demanding change from politicians and convincing the public that climate should be a priority. Buffalo Rebellion, is a coalition of grassroots, labor, and climate justice organizations growing a movement to pass local, state, and national policies that create millions of family-sustaining union jobs—ensuring racial and gender equity and taking action on climate at the scale and scope the crisis demands. It was formed in November 2021 and consists of:

- Iowa Migrant Movement for Justice

- Sierra Club Beyond Coal

- Great Plains Action Society

- DSM Black Liberation Movement

- Cedar Rapids Sunrise Movement

- Iowa CCI

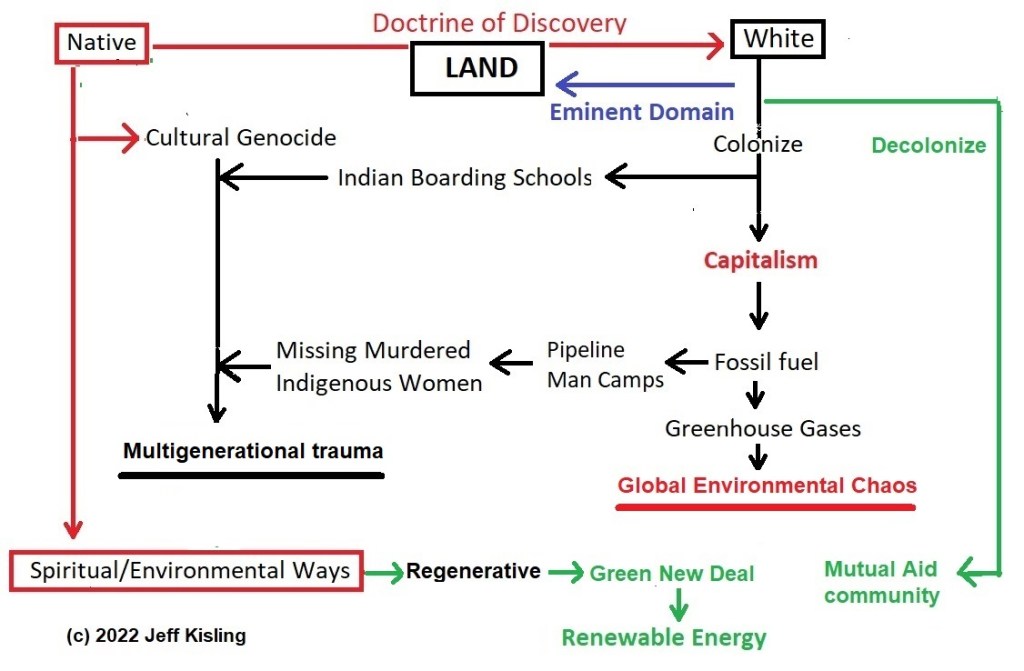

The root causes of what we are fighting against are capitalism and colonialism

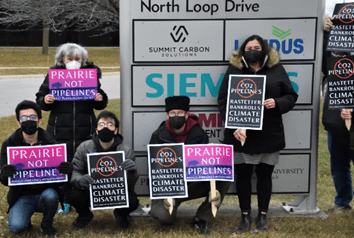

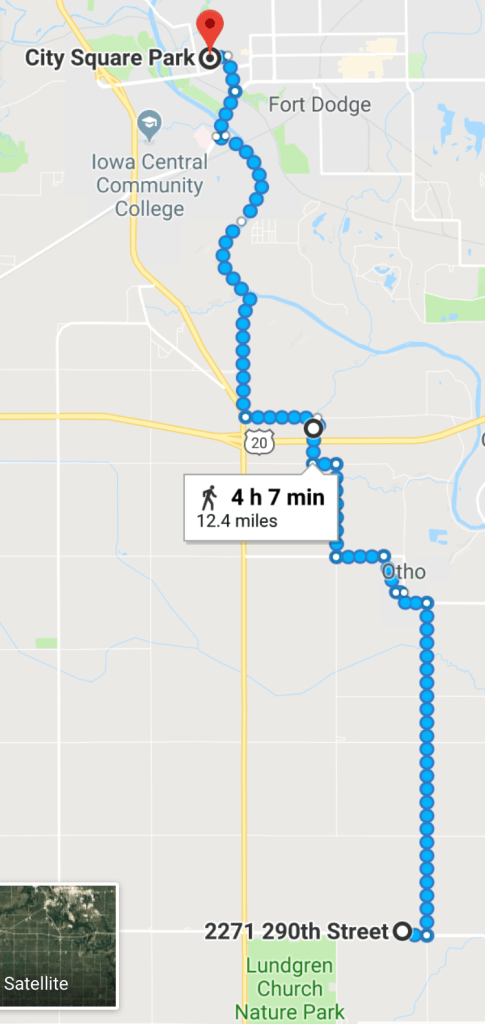

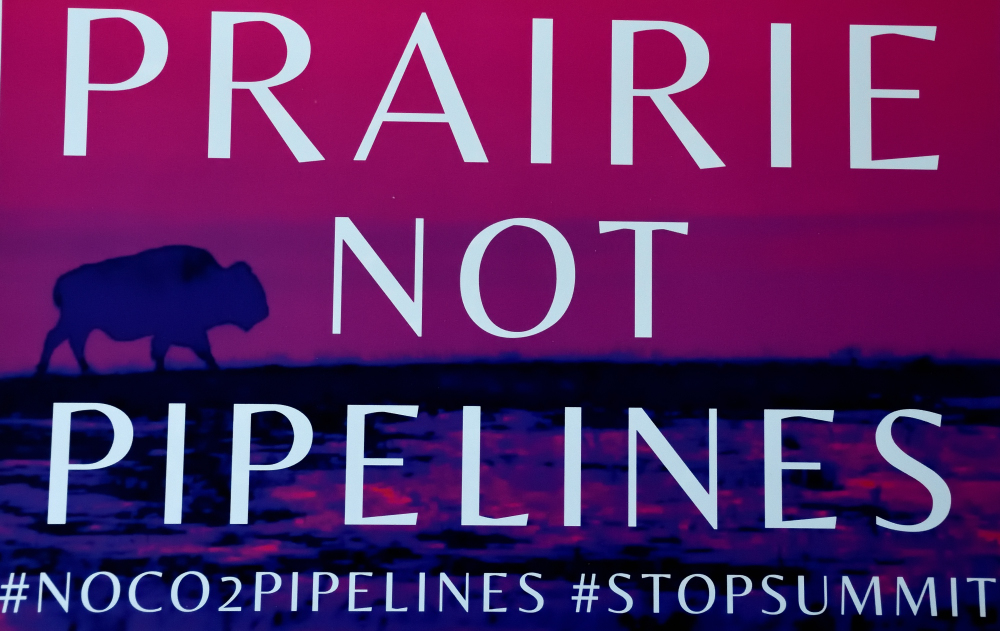

The subject of last night’s gathering (at Iowa CCI and via Zoom) was CO2 (carbon) pipelines, the latest man-made environmental threat. Iowa is at the center of this problem because most of the ethanol plants are located here, because ethanol is produced from corn, and releases carbon emissions in the process. The carbon dioxide in the carbon pipelines is a hazardous material and could cause deaths if there is a rupture. A CO2 pipeline in Satartia, Mississippi ruptured last year, sickening dozens of people. First responders’ vehicles could not run because of the absence of oxygen. READ: “The Gassing Of Satartia” (Huffington Post, August 2021)

Sikowis talked about what is below the crust of the earth also being a sacred space, and we don’t know what disturbing that with pipelines and fracking will cause.

The only way to address fossil fuel emissions is to stop burning fossil fuels.

Mutual Aid

Des Moines Mutual Aid has been the focus of my work for the past couple of years. How is this related to the protection of Mother Earth?

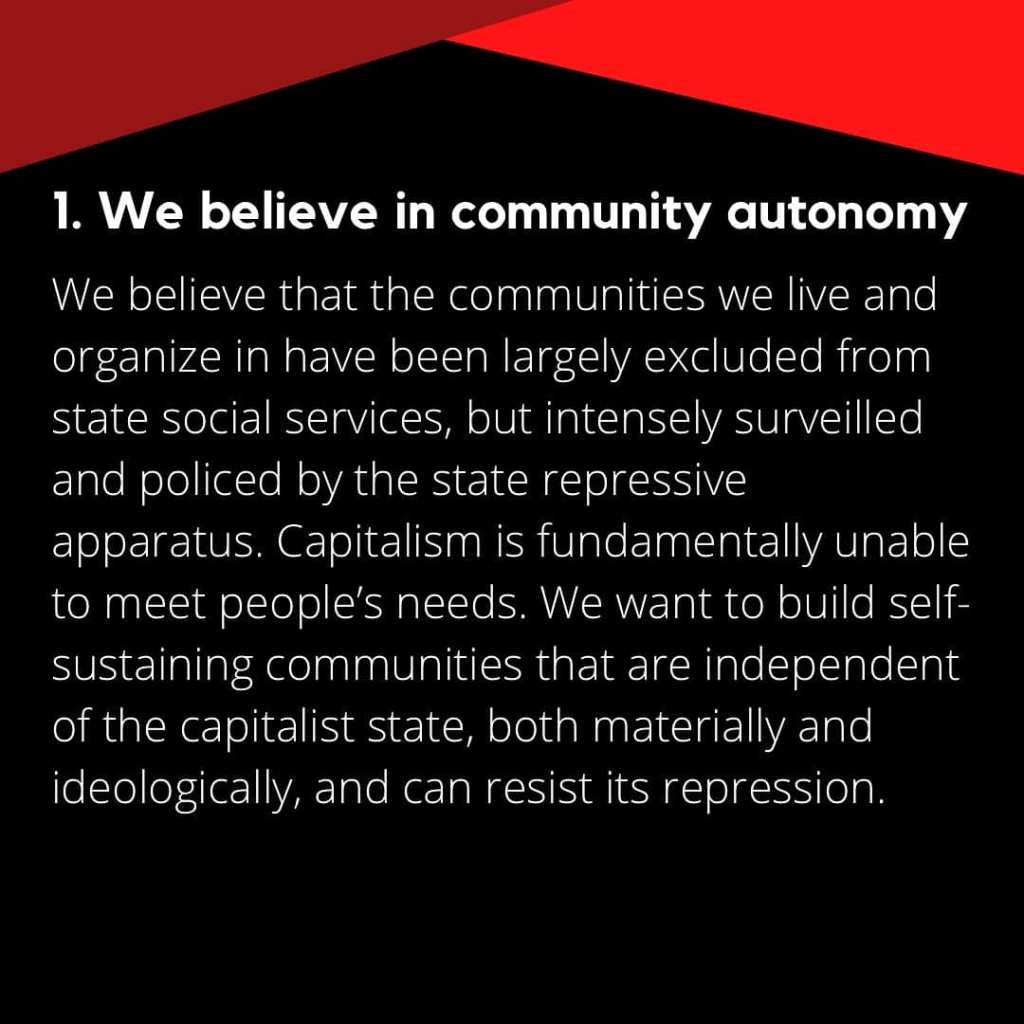

- Being in a Mutual Aid community, we support each other and help each other heal.

- Mutual Aid members are encouraged to use critical thinking to anticipate and solve problems. And immediately implement solutions, not waiting for permission from anyone.

- Mutual Aid is about eliminating vertical hierarchies and the damage those hierarches do to a community. And how they harm Mother Earth.

- Mutual Aid communities are explicitly local. There is no need for fossil fuel transportation and energy production. Our Mutual Aid communities are or will be “walkable”.

- Our Mutual Aid communities are an example to others of how we can escape capitalism and colonialism that are the root causes of injustice

- Our Mutual Aid practices are about sustainability and protection of Mother Earth

- “These spaces become intergenerational, diverse places of Indigenous joy, care and conversation, and these conversations can be affirming, naming, critiquing, as well as rejecting and pushing back against the current systems of oppression”. Maynard, Robyn; Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake.

- “…capitalism and colonialism created structures that have disrupted how people have historically connected with each other and shared everything they needed to survive. As people were forced into systems of wage labor and private property, and wealth became increasingly concentrated, our ways of caring for each other have become more and more tenuous.” Dean Spade

…in Nishnaabeg thinking, knowledge is mobilized, generated, and shared by collectively doing. It’s more than that, though. There is an aspect of self-determination and ethical engagement in organizing to meet our peoples’ material needs. There is a collective emotional lift in doing something worthwhile for our peoples’ benefit, however short-lived that benefit might be. These spaces become intergenerational, diverse places of Indigenous joy, care and conversation, and these conversations can be affirming, naming, critiquing, as well as rejecting and pushing back against the current systems of oppression. This for me seems like the practice of movement-building that our respective radical practices have been engaged with for centuries.

Maynard, Robyn; Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. Rehearsals for Living (Abolitionist Papers) (p. 39). Haymarket Books. Kindle Edition.

In another example of how our work is interrelated, my Mutual Aid friends support the Wet’suwet’en.

Wet’suwet’en

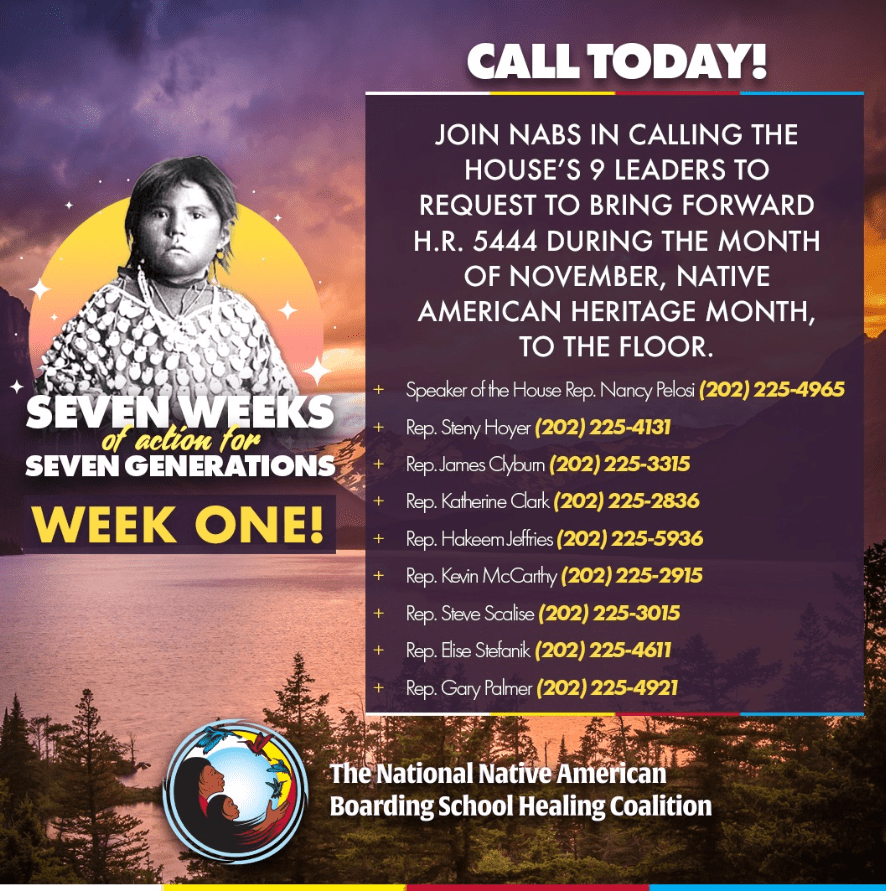

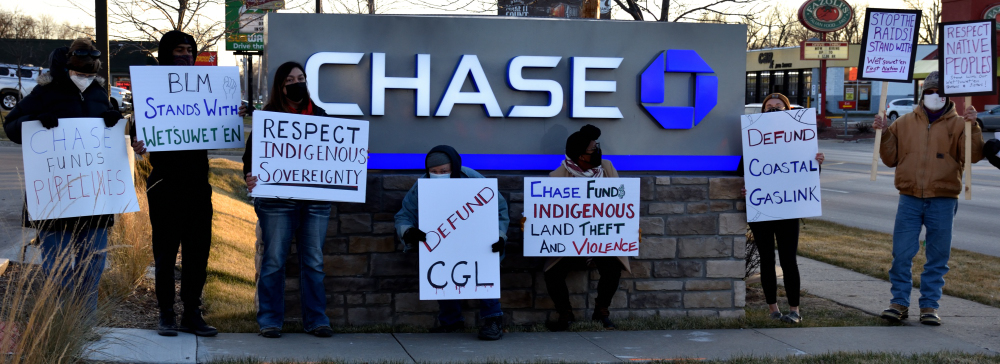

The Wet’suwet’en peoples have been struggling for years to prevent the construction of the Coastal GasLink liquified natural gas pipeline from being built through their pristine, unceded lands.

https://quakersandreligioussocialism.com/?s=wetsuweten+wet%27suwet%27en

https://jeffkisling.com/?s=wetsuweten+wet%27suwet%27en

There was one particularly significant Spirit-led event in my life related to the Wet’suwet’en. When I first became involved with the Wet’suwet’en peoples was when they were asking allies to spread the news about their struggles, since there was no mainstream media coverage.

In February 2020, some of us were already planning to be at Friends House in Des Moines. We decided to hold a vigil for the Wet’suwet’en on the street in front of Friends House prior to that meeting. I created an event announcement on Facebook, that was shared by my friend Ed Fallon or Bold Iowa, an Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement.

As anticipated just those few of us who were planning to attend the meeting at Friends House anyway showed up. But the Spirit-led part of this is that Ronnie James, who I didn’t know at the time, joined us. Ronnie is an Indigenous organizer with twenty years of experience. He was surprised anyone in Iowa knew about the Wet’suwet’en peoples, so he came to see who was attending, a good organizing technique.

Ronnie and I began to exchange messages over the next couple of months. I was intrigued with the stories he was telling me about Des Moines Mutual Aid community he was involved with. When I felt we had begun to know each other well enough, I tentatively asked if I could attend the food giveaway that Ronnie/Des Moines Mutual Aid held every Saturday morning. This was a continuation of a variation of the Black Panther Party’s free school breakfast program in Des Moines from the 1970’s.

I thought I would just attend a time or two to see how that worked. Instead, I’ve been there almost every Saturday morning for over two years now, and Ronnie is one of my best friends. One of the many good things about Mutual Aid is how it attracts and keeps people engaged.

I continue to do what I can to support the Wet’suwet’en. We are presently organizing another gathering at Chase bank to call attention to their funding fossil fuel projects. Some others from the Buffalo Rebellion will be involved.

Bear Creek Friends Meeting

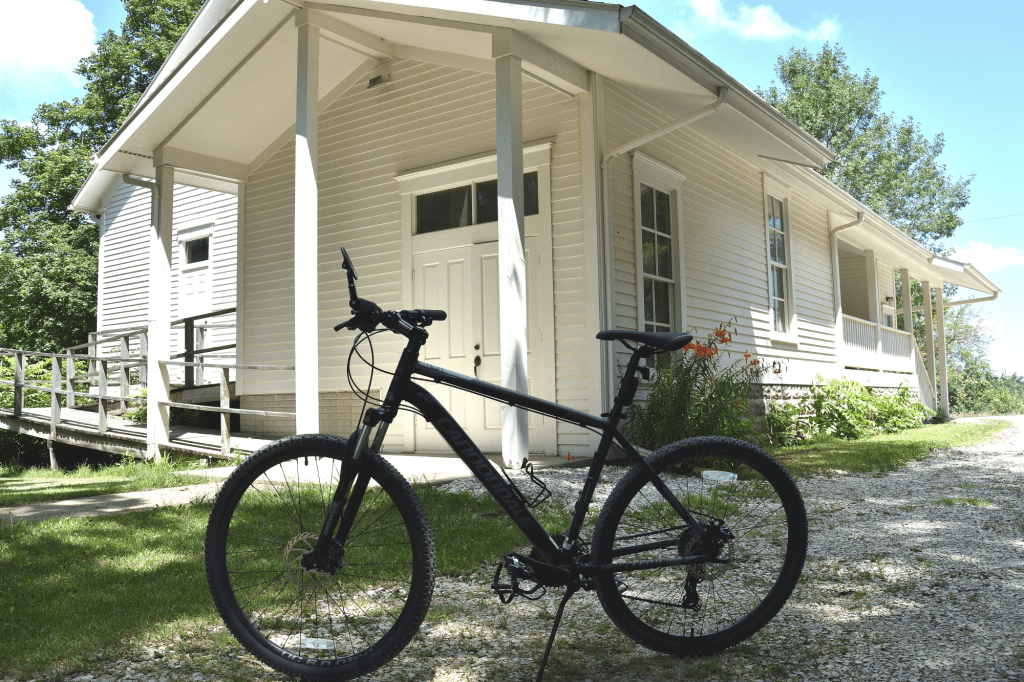

The small, rural Quaker meeting I’m a member of continues today to try to find ways we can help protect Mother Earth. This is one way to bring a Spiritual approach to these problems which I believe is very important.

Members of the meeting have supported the annual Prairie Awakening/Prairie Awoke ceremony that takes place at the Kuehn Conservation Area, just a few miles from the meetinghouse.

Bear Creek Friends Meeting

It is difficult to reduce fossil fuel use in rural areas.

One thing we realized we could do was encourage more use of bicycles, since many members lived close to the meetinghouse just north of Earlham, Iowa. And encourage Friends in urban meetings to use bicycles when possible.

The Minute we wrote, and that was approved by Iowa Yearly Meeting of Friends (Conservative) was referred to as a Minute on “Ethical Transportation”.

Radically reducing fossil fuel use has long been a concern of Iowa Yearly Meeting (Conservative). A previously approved Minute urged us to reduce our use of personal automobiles. We have continued to be challenged by the design of our communities that makes this difficult. This is even more challenging in rural areas. But our environmental crisis means we must find ways to address this issue quickly.

Minute approved by Iowa Yearly Meeting (Conservative) 2017

Friends are encouraged to challenge themselves and to simplify their lives in ways that can enhance their spiritual environmental integrity. One of our meetings uses the term “ethical transportation,” which is a helpful way to be mindful of this.

Long term, we need to encourage ways to make our communities “walkable”, and to expand public

transportation systems. These will require major changes in infrastructure and urban planning.

Carpooling and community shared vehicles would help. We can develop ways to coordinate neighbors needing to travel to shop for food, attend meetings, visit doctors, etc. We could explore using existing school buses or shared vehicles to provide intercity transportation.

One immediately available step would be to promote the use of bicycles as a visible witness for non-fossil fuel transportation. Friends may forget how easy and fun it can be to travel miles on bicycles. Neighbors seeing families riding their bicycles to Quaker meetings would have an impact on community awareness. This is a way for our children to be involved in this shared witness. We should encourage the expansion of bicycle lanes and paths. We can repair and recycle unused bicycles, and make them available to those who have the need.