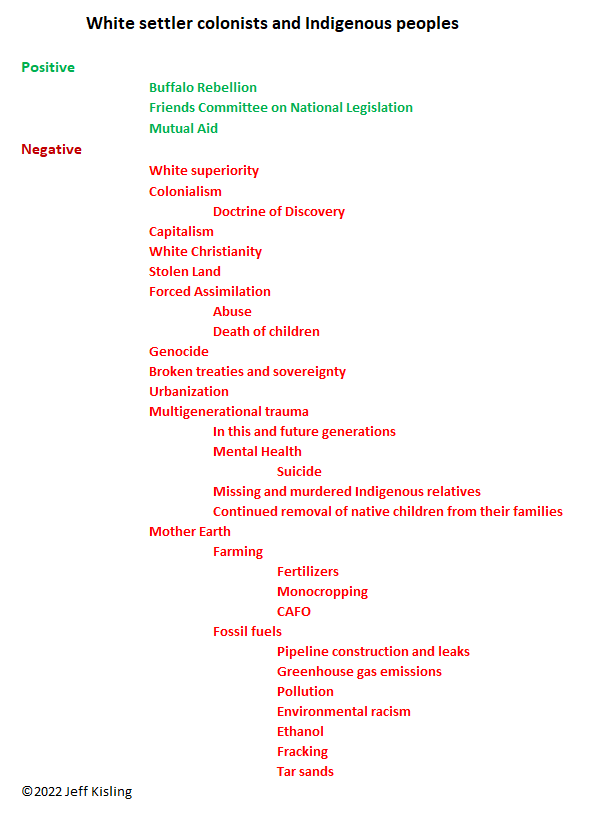

Truthsgiving is about the holiday known by many non native people as Thanksgiving. A day when families gather together. Family gatherings are wonderful. Unfortunately, the myth of a peaceful gathering of settler colonists and Indigenous peoples comes up.

I didn’t think I would write about this today. Didn’t want to bring negativity to joyful gatherings. But the Spirit is telling me to share this, this plea to at the least not whitewash the history.

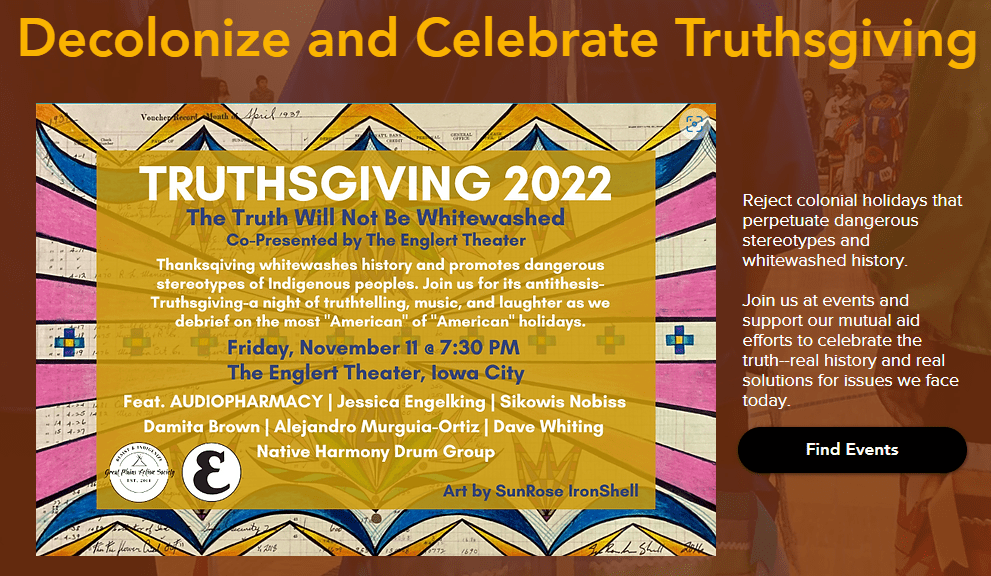

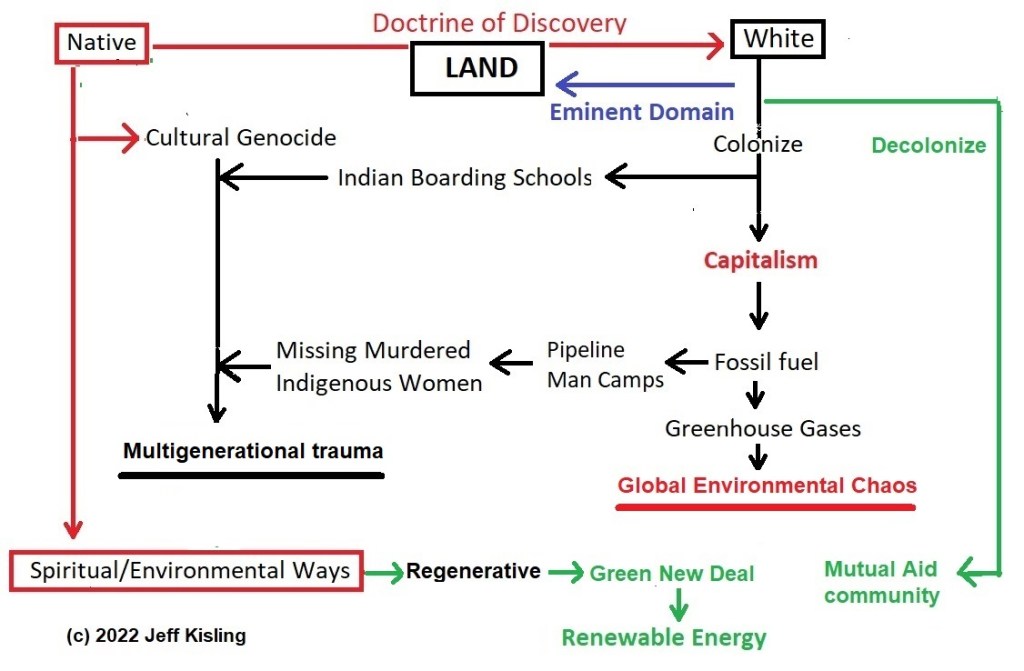

The term Truthsgiving is about the opportunity to spread awareness about the true history, about the genocide and land theft from Indigenous peoples by white settler colonists.

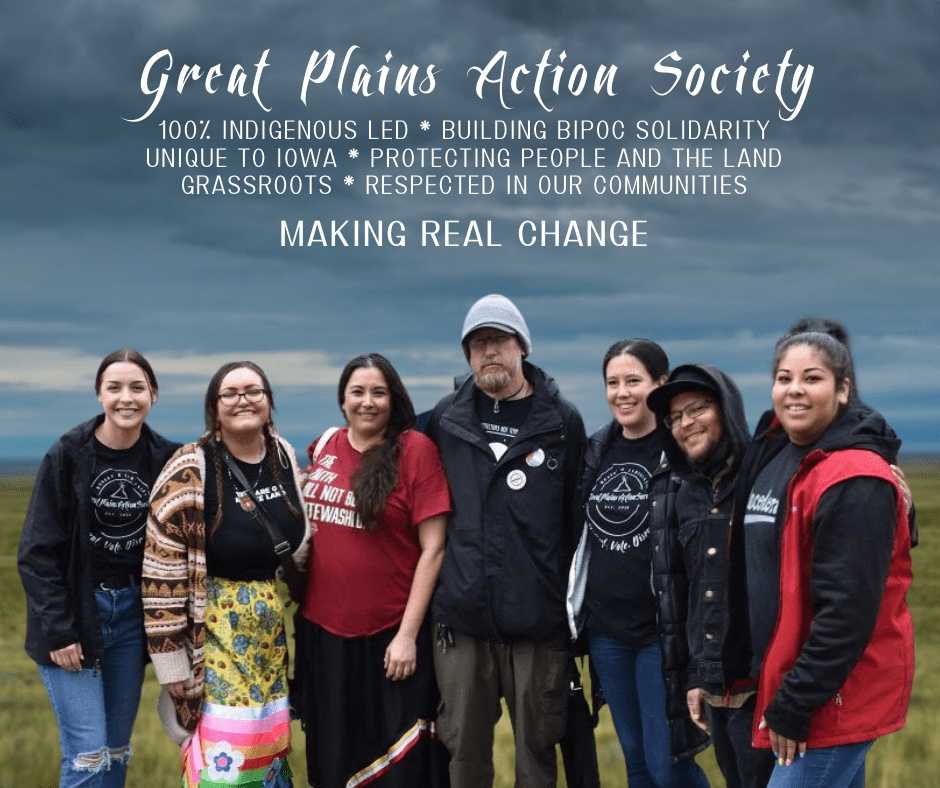

Truthsgiving is an ideology that must be enacted through truth telling and mutual aid to discourage colonized ideas about the thanksgiving mythology—not a name switch so we can keep doing the same thing. It’s about telling and doing the truth on this day so we can stop dangerous stereotypes and whitewashed history from continuing to harm Indigenous lands and Peoples, as well as Black, Latinx, Asian-American and all oppressed folks on Turtle Island. https://www.truthsgiving.org/about

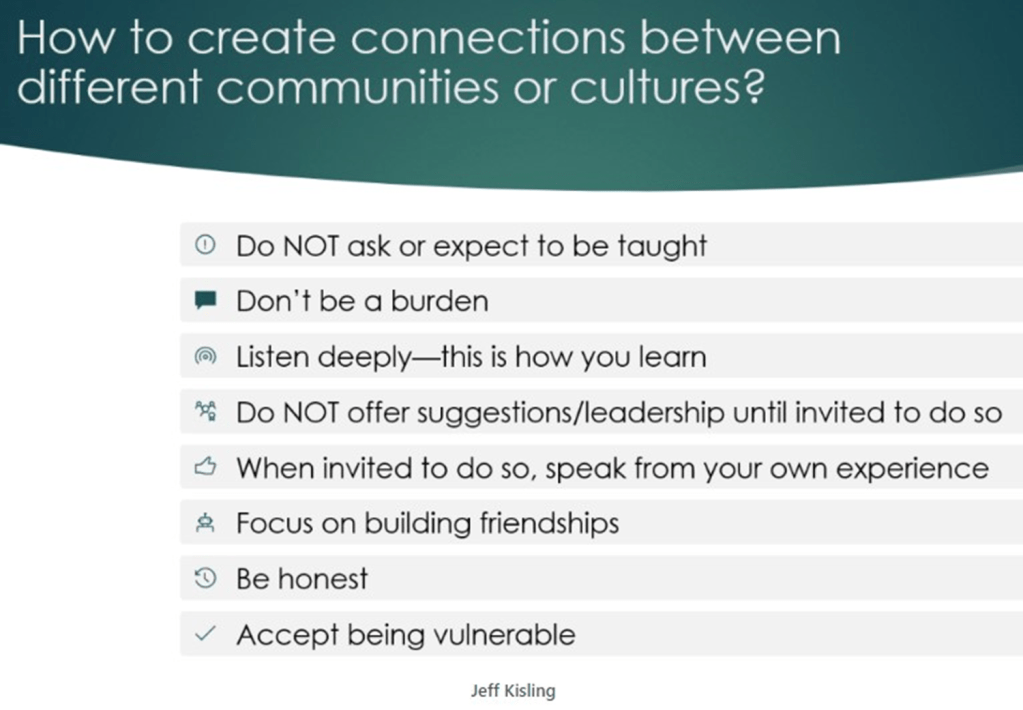

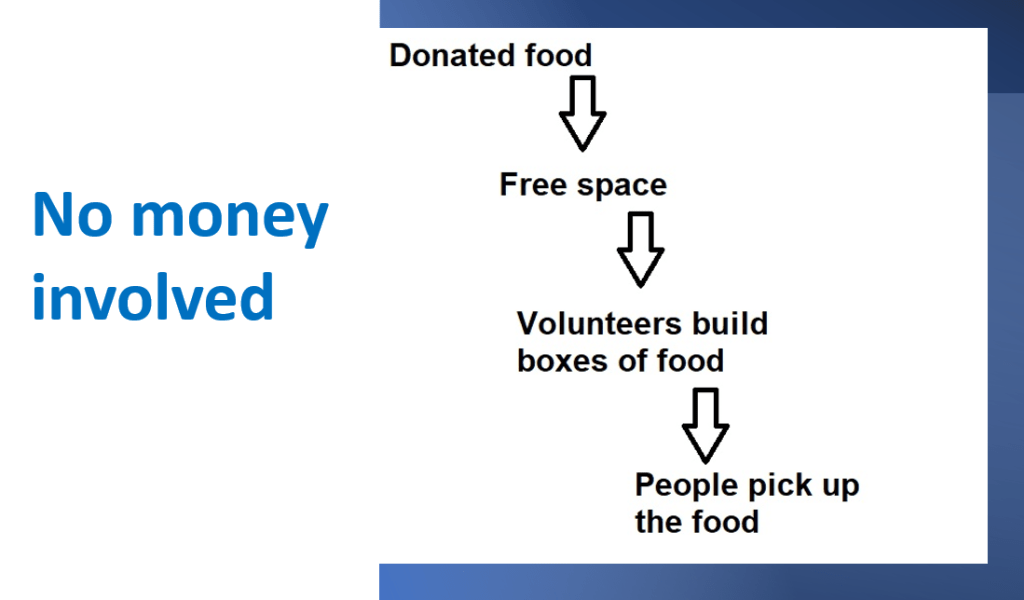

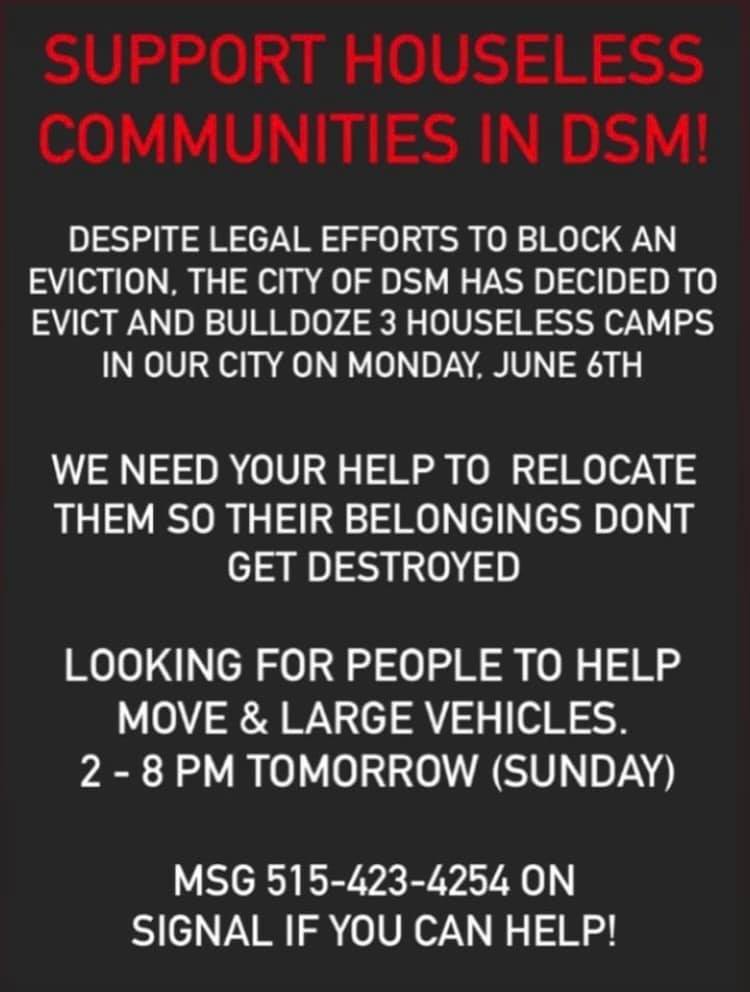

If there is an opportunity for truth telling, there will probably be questions about what to do about this. That’s where mutual aid comes in. I was blessed to be led to connect with Des Moines Mutual Aid and have written a lot about that. https://quakersandreligioussocialism.com/mutual-aid/

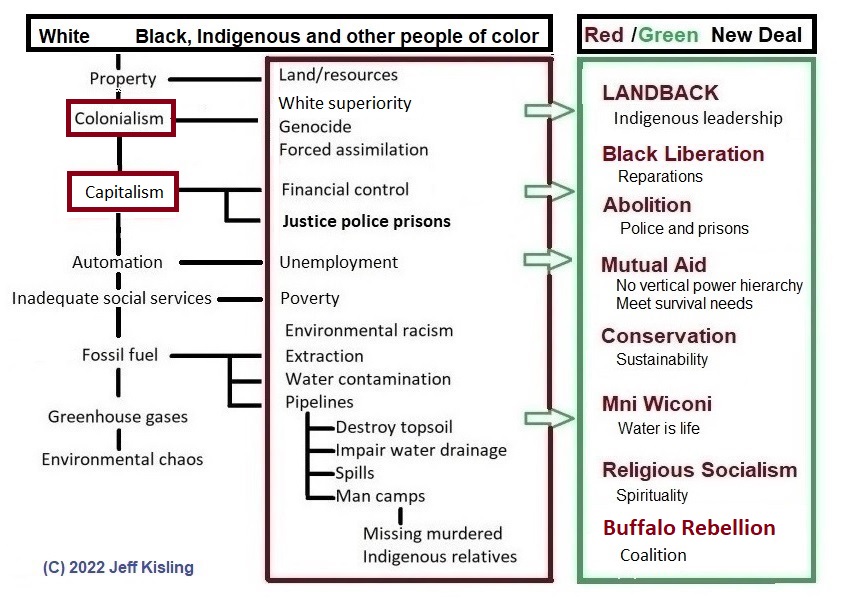

The reason mutual aid is important is because it provides an alternative to the capitalism and white superiority that our mainstream society is built upon. Mutual aid can help us Walk a Path of Doing the Truth as my friend Ronnie James wrote in “Doing Truth When the World is Upside Down.”

To walk a path of Doing the Truth

To walk a path of Doing the Truth is a battle with a very young culture. Telling the truth is comparably easy, we have our oral histories, art and traditions created and carried on, histories printed by those that found a way to the presses. We can recount the stories and lessons that survived colonialism.

But to do the truth, to live a life that enforces what we once had, a life and culture that made a millennia of humanity possible to thrive, is to be at war with what has defined and destroyed this world for too long.

Doing Truth When the World is Upside Down by Ronnie James, TRUTHSGIVING, Nov 18, 2020

Truthsgiving is an ideology that must be enacted through truth telling and mutual aid to discourage colonized ideas about the thanksgiving mythology

TRUTHSGIVING. The Truth will not be whitewashed

Des Moines Mutual Aid Points of Unity

0. We believe in working shoulder to shoulder and standing in solidarity with all oppressed communities. We ourselves are oppressed, and our mutual aid work is a fight for our collective liberation. We do not believe in a top-down model of charity. Instead, we contrast our efforts at horizontal mutual aid, the fostering of mutually beneficial relationships and communities, to dehumanizing and colonizing charity.

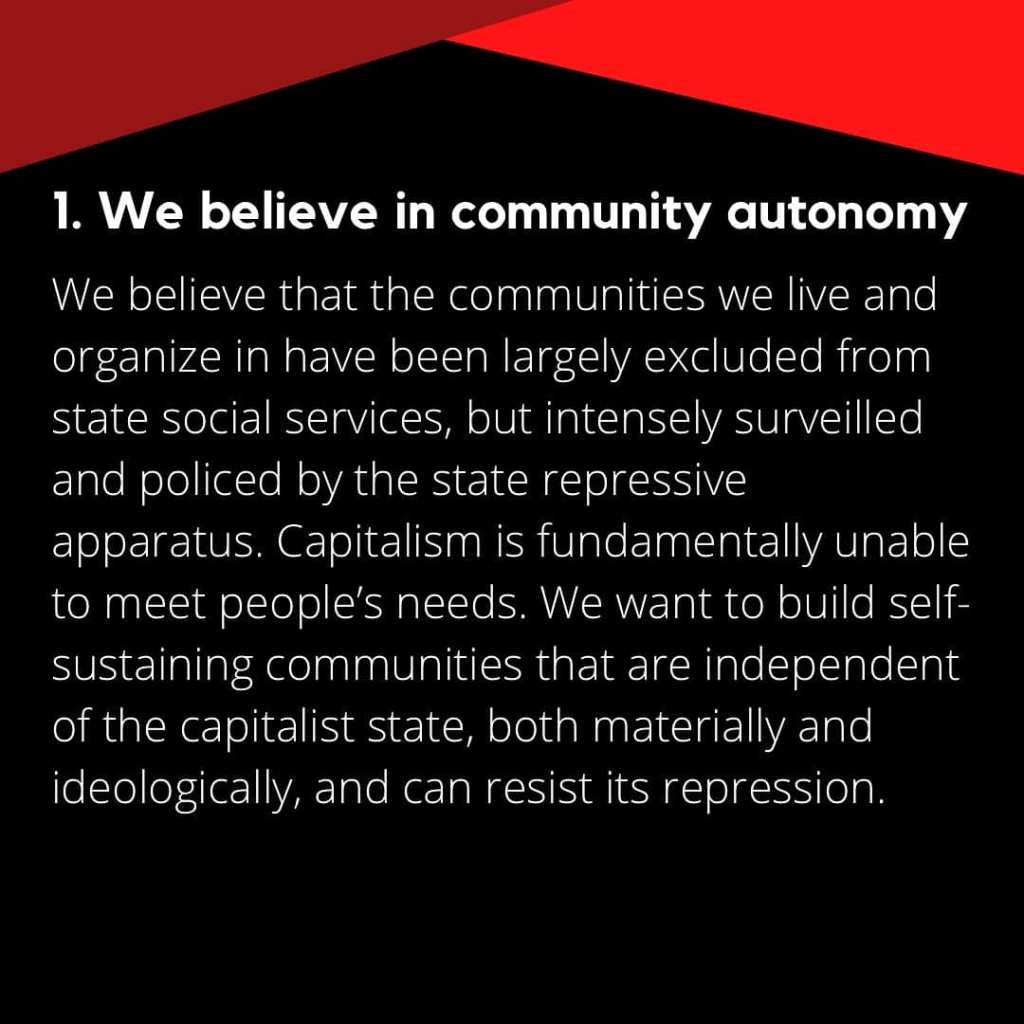

1. We believe in community autonomy. We believe that the communities we live and organize in have been largely excluded from state social services, but intensely surveilled and policed by the state repressive apparatus. Capitalism is fundamentally unable to meet people’s needs. We want to build self-sustaining communities that are independent of the capitalist state, both materially and ideologically, and can resist its repression.

2. We are police and prison abolitionists. Abolition and the mutual aid that we practice are inextricably linked. We don’t rely on capitalist institutions or the police to do our work. We believe in building strong and resilient communities which make police obsolete, including community systems of accountability and crisis intervention.

3. We work to raise the political consciousness of our communities. Part of political education is connecting people’s lived experiences to a broader political perspective. Another component is working to ensure that people can meet their basic needs. It is difficult to organize for future liberation when someone is entrenched in day-to-day struggle.

4. We have open disagreements with each other about ideas and practices. We believe there is no formula for resolving our ideological differences other than working towards our common aims, engaging with each other in a comradely manner, and respecting one another, whether or not we can hash out disagreements in the process.

Des Moines Mutual Aid is an Abolitionist Mutual Aid Collective made up of varying radical and revolutionary tendencies in what is current known as central iowa.

None of these articles represent the collective as a whole. Take what you can from these pieces and burn the prisons.

In Love and Rage,

Des Moines Mutual Aid