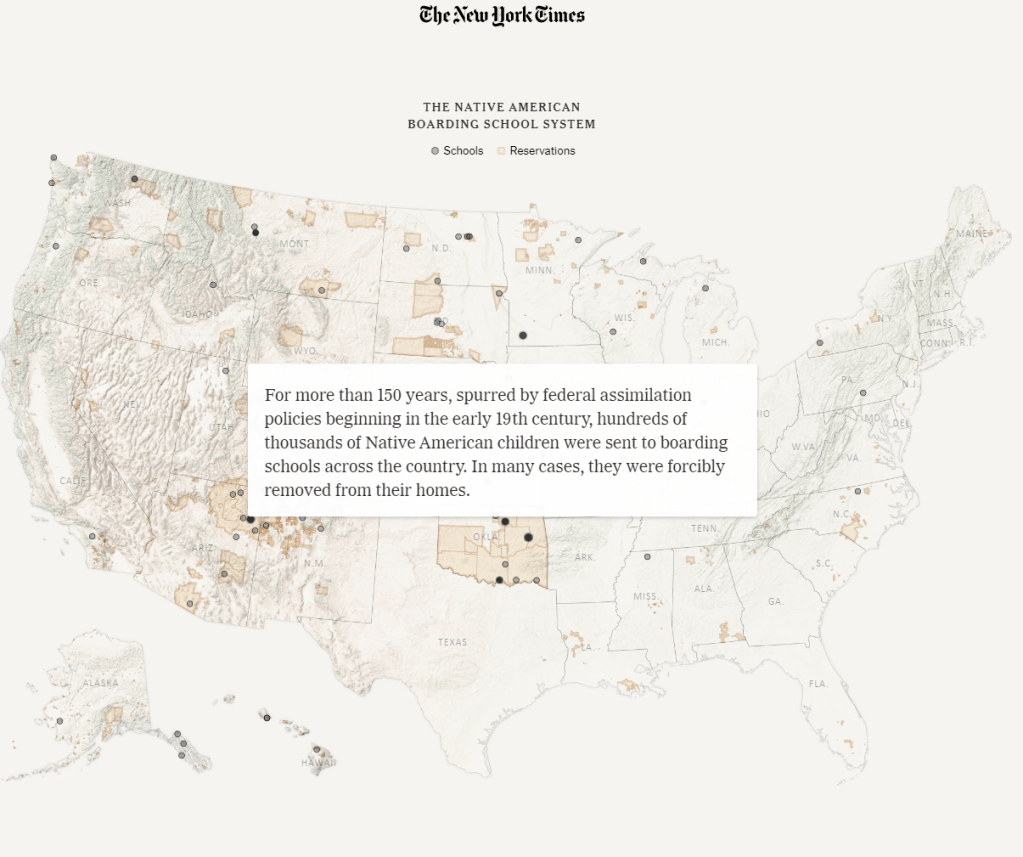

My friends at the Great Plains Action Society (GPAS) have done a lot of work to call out the whitewashed history of Thanksgiving, one of many colonial mythologies about Indigenous Peoples and the founding of the US and Canada, which I wrote about yesterday.

But of course, there is nothing wrong with reflecting on what we are thankful for.

I am grateful for many things.

My first thought went to something I recently heard someone say. That he was a draft resister in the Vietnam War era, and that was the best thing he’d ever done. I was astonished to hear that fifty years later. I know what he was saying because I was a draft resister then, as well. As an 18-year-old, I knew this decision would set the course of my life. It would be easy to accept conscientious objector status and do two years of alternative service. Fortunately, though, I was aware of the stories of many Quaker men I knew who refused to participate in the war machine. Knowing they risked imprisonment and often were. But I saw how that choice defined the rest of their lives.

It was a clear choice that Robert Frost’s poem, The Road Not Taken, tells so eloquently.

At that same time, I found I had another decision to make. Moving to Indianapolis, I was horrified by the noxious clouds of smog pouring from every tailpipe; this was before catalytic converters covered up the damage being done to Mother Earth. I made another decision that was definitely a road less traveled (so to speak): to live without a car. That was another of the best decisions of my life, defining so much of what happened thereafter. Affecting every day of my life as I was able to witness the wonder of what I was walking through.

So the phrase ‘Now shall I walk, or shall I ride?’ in Metaphors of Movement caught my attention.

The Best Friend

Now shall I walk

Or shall I ride?

“Ride”, Pleasure said;

“Walk”, Joy replied.

William Henry Davies

1871 – 1940

In his 1914 poem The Best Friend, the Welsh poet and occasional vagabond W.H. Davies pondered a timeless question: “Now shall I walk, or should I ride?” This seemingly simple dilemma encapsulates the modern industrial choice between slow-paced ageless wandering on foot or embracing the thrill of motorized transport, along with the attendant speed and freedom it offers, which has become such an integral part of our contemporary lifestyle. It likewise speaks volumes about us and about the nature of the choices we make daily.

Gone perhaps are the days of poetic musings over the merits of walking versus riding. Yet one can’t help but wonder if we have lost something essential along the way—a connection with the world that only a leisurely walk can provide.

C.S. Lewis, while growing up in the outskirts of Belfast, Northern Ireland, counted it among his blessings that his father had no car, so the deadly power of rushing about wherever he pleased had not been given to him. He thus measured distance by the standard of a man walking on his two feet and not by the standard of the internal combustion engine, for it is here where both space and time is annihilated by the deflowering of distance. In return, he possessed “infinite riches” in comparison to what would have been to motorists a “little room.” Key to those riches was what he came to call, and experience throughout life as, “joy,” and walking became a portal through which he sought it. A participatory engagement with life and living which I contend is as vital to our survival as breathing itself.

Metaphors of Movement by Keith Badger, Parabola, Nov 22, 2023

“I hope that in this year to come, you make mistakes. Because if you are making mistakes, then you are making new things, trying new things, learning, living, pushing yourself, changing yourself, changing your world. You’re doing things you’ve never done before, and more importantly, you’re doing something.”

Neil Gaiman

The Road Not Taken

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.I shall be telling this with a sigh

Robert Frost

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

This is a link to my photos of the Vietnam War Memorial. https://jeffkislingphotography.wpcomstaging.com/2023/11/17/washington-dc/nggallery/washington-dc/vietnam-war-memorial