Sometimes, I miss what is most obvious. I’ve been writing (a lot) about T-MAPs (https://quakersandreligioussocialism.com/t-maps/)

Yesterday (T-MAPs and YOUR own story) I said ‘I sense that I’ve written enough about Transformative Mutual Aid Practices (T-MAPs).’

This morning, I was feeling chaotic, I guess I might say. I won’t present the long list of my concerns. I’m sure we share many of them, especially related to the potential for global war. You might see where this is going. I realized I needed to revisit MY OWN Transformative Mutual Aid Practice document, which I had created less than a year ago. (That’s the obvious thing I realized this morning).

I can see what I did previously because when you use the online tool, you can choose to have your answers emailed to you. The alternative is to download the sections, print them, and write your answers on the forms.

I moved the conclusion to this beginning because it summarizes why T-MAPs can be a tool for Mutual Aid.

Conclusion – T-MAPs as a Tool for Mutual Aid

We hope the process of completing your T-MAP has given you new insights into your own story and inspiration to engage in this process with others. It’s a living document – you can keep revising it and adding to it as you gain more ideas and visions. While T-MAPs can help you map your individual transformation and growth, we think it’s more powerful as a collective practice. T-MAPs is a tool that is designed to be developed in groups, shared with groups, and practiced in groups. Our vision is that T-MAPs and tools like it will play an important role in evolving the ability of creative activist movements and mental health support networks to communicate with each other and build the kinds of stronger, more effective communities and forms of resistance that our current historical moment requires.

By reflecting deeply on our own experiences and developing a stronger connection with ourselves and what’s important to us, we can become more comfortable sharing that knowledge; we can learn from each other and more easily collaborate with one another. By having a better awareness of each other’s personal struggles, it’s easier to understand our similarities and differences and navigate them with respect, love, and understanding. T-MAPs is really our attempt to help operationalize mutual aid.

Crisis = Opportunity

Taking the time to articulate basic needs and desires about wellness and support when someone is in a clear head space can make an enormous difference when any kind of crisis emerges. Having others who already know what your needs and desires are can turn crisis into an opportunity for growth and transformation, for building solidarity and grounded friendship. Understood and articulated, our weaknesses can actually become our strengths.

At the same time, by opening up space to talk about life lessons and personal stories it can become easier to talk about collective dynamics, and things that are often challenging to talk about in groups, like power and larger structures that affect all of us in different ways depending on our social location, like race and class and gender and ability. While there are many ways that our differences can end up separating us, if we can learn to talk about the difference our stories can actually bring us together and raise levels of awareness. T-MAPs is an invitation to a collective practice of transformation and growth. Skillfully facilitated, a group using these questions can evolve to trust and support each other in the hard times on the horizon.

T-MAPs Section 1: Connection and Vision

The purpose of this first section is to help ground us in our strength and resilience before we undertake the T-MAPs process. To reframe the conversation so that it’s not starting from the premise that we are sick and need fixing; instead, we are reminded of what we are like when we’re well — how it feels and how we relate to the world around us. Taking the time to think about these things is generative: this is less like a form to fill out where we already know the answers and more a starting point to prompt our imaginations.

This is the format of the tool. To introduce each topic and provide checkboxes to help you answer the question, in this case, How do I feel when I’m most alive? And then a free-form box to describe your own experiences.

These were my answers at that time:

There are more pages in this section, but I think you get the idea.

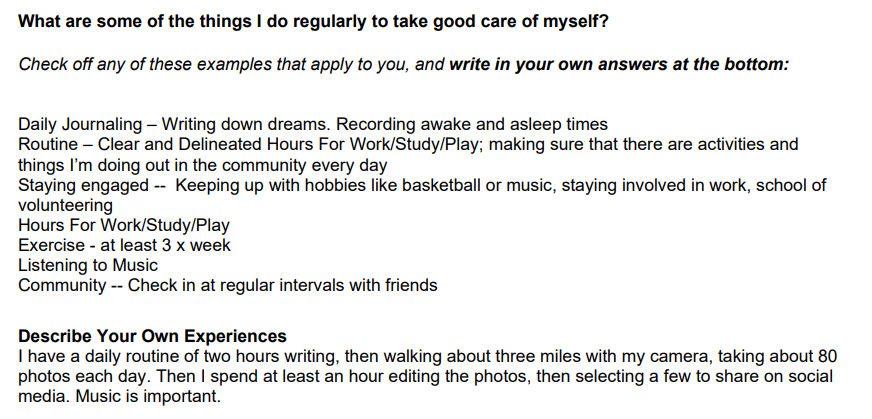

Section 2: Wellness Practices

This section is designed to guide us in building our wellness toolkit – to identify what practices and supports help us manage stress, avoid crisis, and stay grounded and healthy. Once we’ve developed these lists, it is good to return to them on a daily basis and potentially share them with others in our lives. If we notice we’re slipping off track, we can return to this toolbox to help us remember how to get back on course.

My answers

And, again, there are multiple questions in this section.

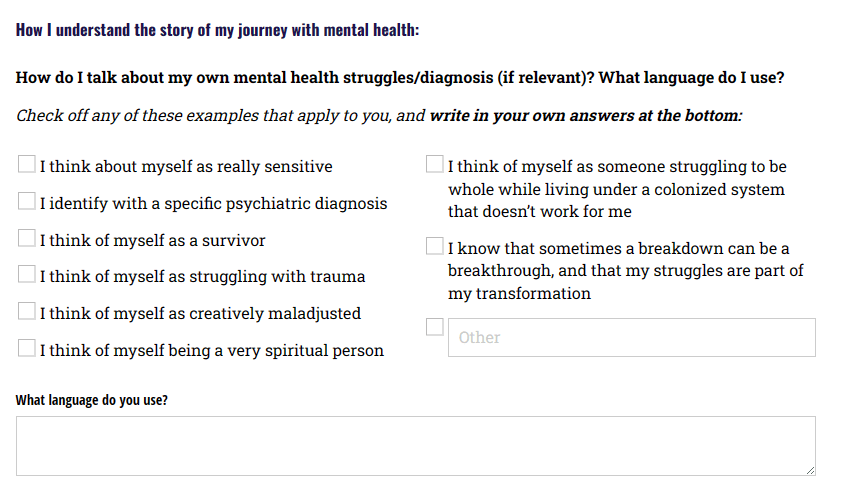

Section 3: Life Lessons and Personal Stories

Where we come from and how we tell stories about ourselves is so important. In this section we have a series of questions to help you think about your own personal story and find good language for it. Society has so many expectations and frameworks for understanding your life that might not fit at all, or might fit in some ways but not others. There is an incredible power in creating a personal narrative of your life that fits well for you.

This section has two parts – the first is on understanding your journey with mental health and emotional distress, and the second on social and cultural context as it informs mental health. If you don’t identify as someone who’s been through intense mental health struggles and and/or the diagnosis process, some of the questions in the first half might not feel like they apply – it’s fine to skip them. In the second half of this section, some of these questions might be new to you – you might not have thought a lot about your cultural or class background, for example – and that’s ok. Consider these questions a starting point for your explorations.

How I understand the story of my journey with mental health:

My answers

I think of myself as creatively maladjusted

I think of myself being a very spiritual person

I think of myself as someone struggling to be whole while living under a colonized system that doesn’t work for me

What language do you use?

I think of myself being a very spiritual person. My spirituality is a very important part of my mental health. And language is important because in my culture we don’t have good ways to express spirituality.

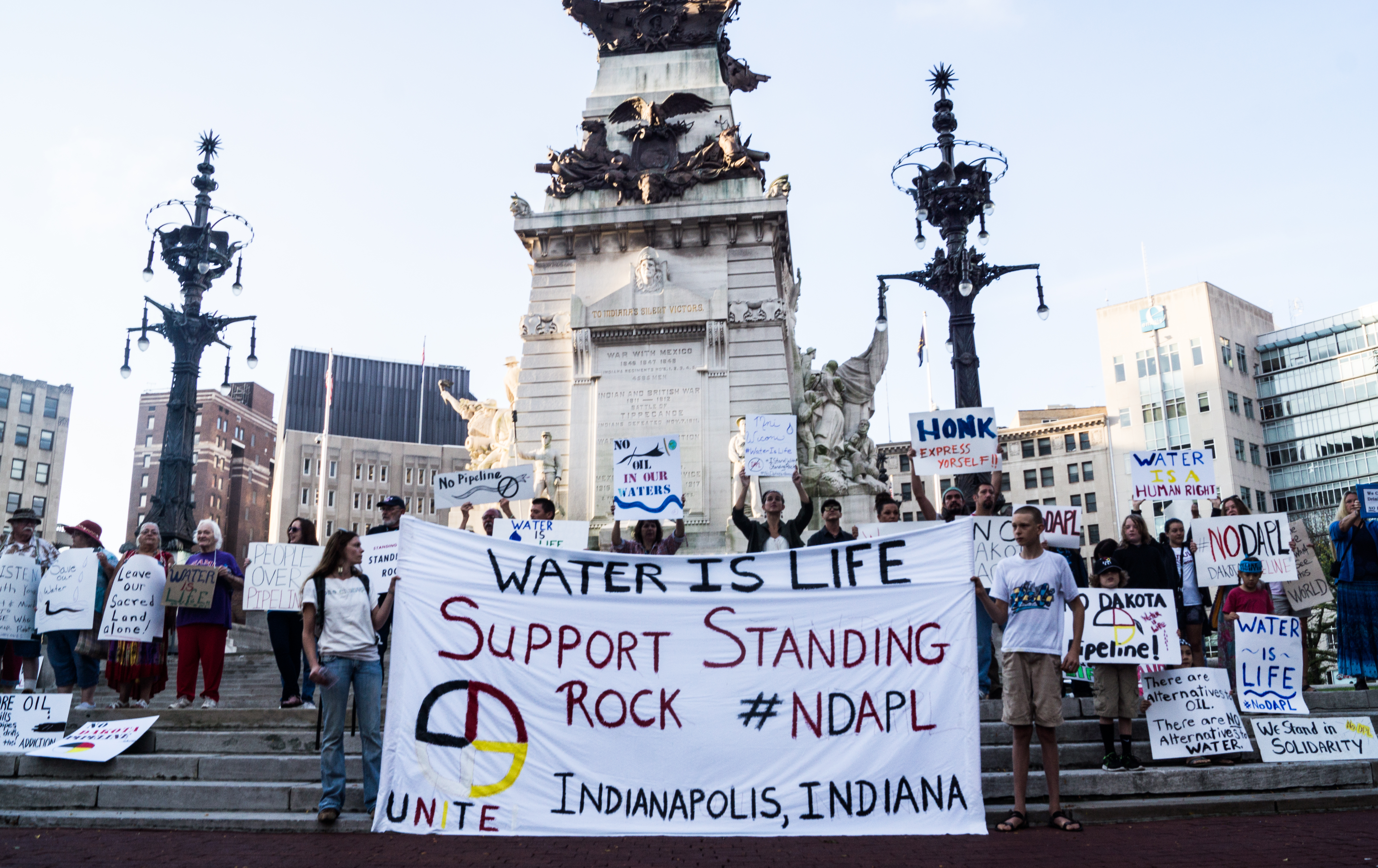

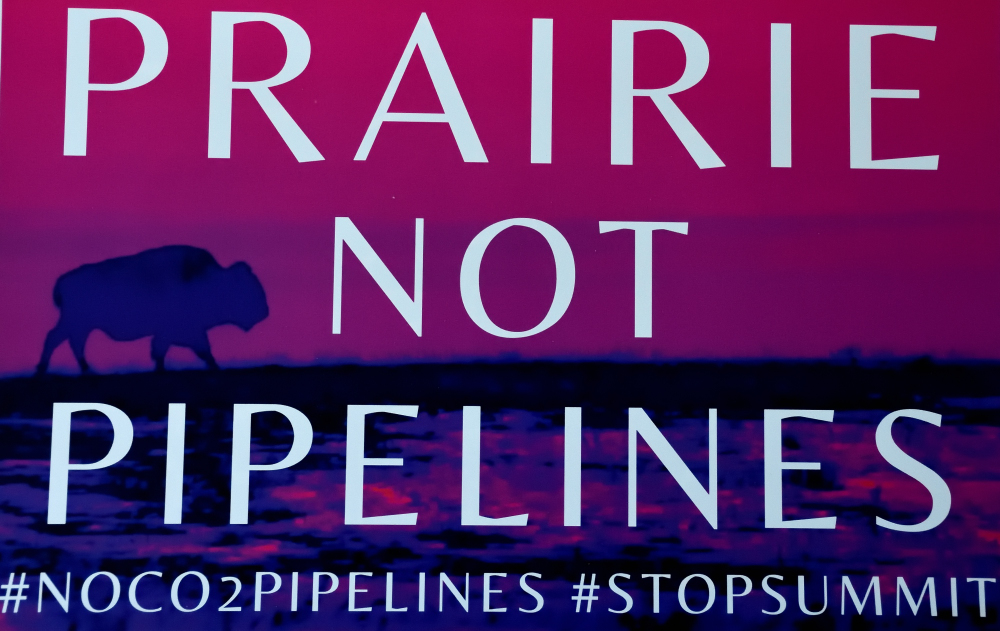

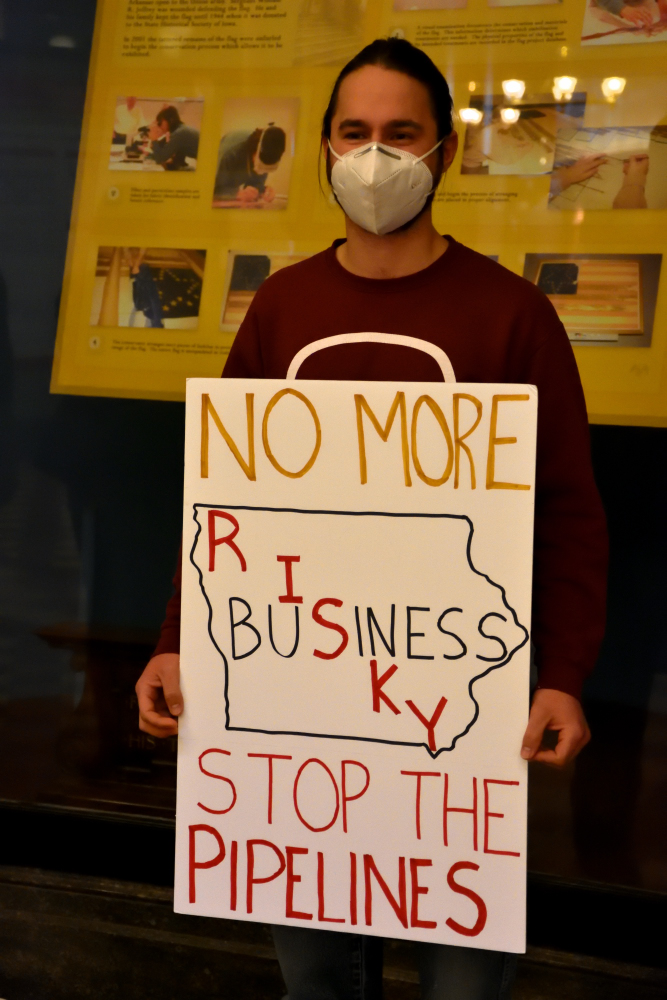

I have been learning a lot about settler colonialism from my Indigenous friends. While I continue to learn of all the ways I benefit from white superiority, life as a Quaker has meant many struggles against white dominance. At 18 years of age, I became a draft resister. I was led to live my life without a car for environmental reasons. I’ve spent the past decade working to protect the water, working against pipelines.

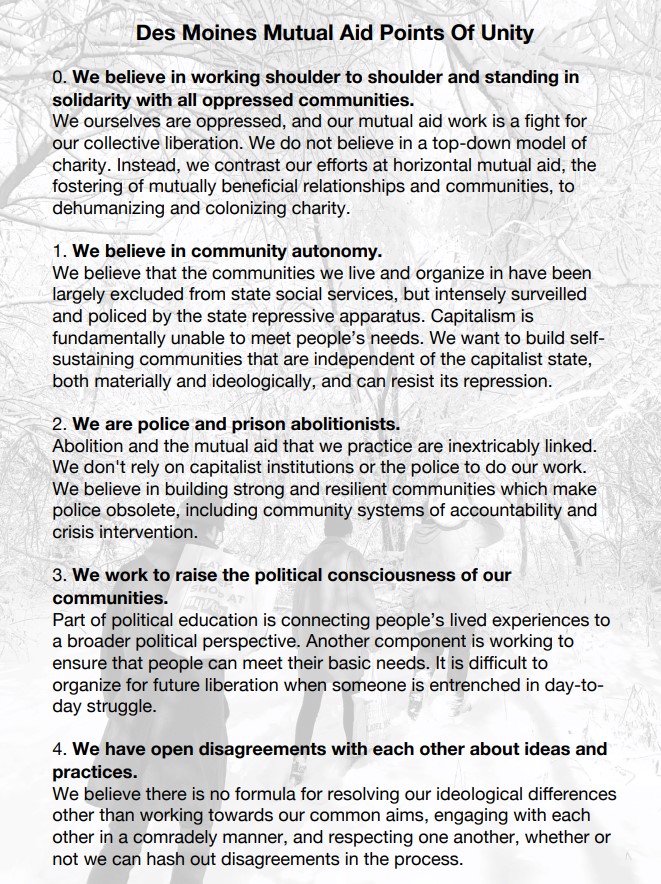

I’ve found a home in my Mutual Aid community that works against systems of dominance and hierarchy.

If I’ve been through serious crisis, what were some of the early indications that I was struggling? How did it all happen?

There has always been something different about me

The truth is I never really felt like I fit in

Add your own:

Quakers used to be referred to as a peculiar people, often refusing to accept the norms of the culture we live in. Living without a car was one of the most visible expressions of that. That periodically created real crisis for me, because it was not only a struggle to live without a car, but this caused conflict with my fellow Quakers, the people I looked to for support, and to be examples of faith in the wider community.

And as I learned more about racism during the years I spent in a Black youth mentoring community, it became a real conflict to find so many Quakers had no idea of their white privileges, and the ways racism was part of their lives.

Over the past five years of making and developing friendships with Indigenous people, I’m learning much more about the multigeneration traumas they, and their ancestors have from the genocide of their people as their land was stolen and millions were killed as White people moved across the country.

Again, white Quakers were involved in some of this when they were involved in the forced assimilation of native children. Native children were kidnapped from their homes and taken to institutions where horrendous things were done to try to erase their Indigenous culture and become more like white people.

Over 100,000 children were forced to go to these institutions where there was widespread physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. Thousands died. It is a struggle to be with my Indigenous friends, knowing of this history, as it must be for them to have me in their presence. And it has been another source of significant trauma to me to not only know that, but once again for so many White friends to work so hard to refuse to think about this history, let alone do anything they can to begin any process of healing.

And over the past three years as part of my Mutual Aid community, I see more clearly the systems of white dominance at every level. Learn more about these things in myself. And struggle again to get other white Quakers to understand this and do something about it.

In fairness I must say there are white Quakers who do acknowledge these things and are working to improve them

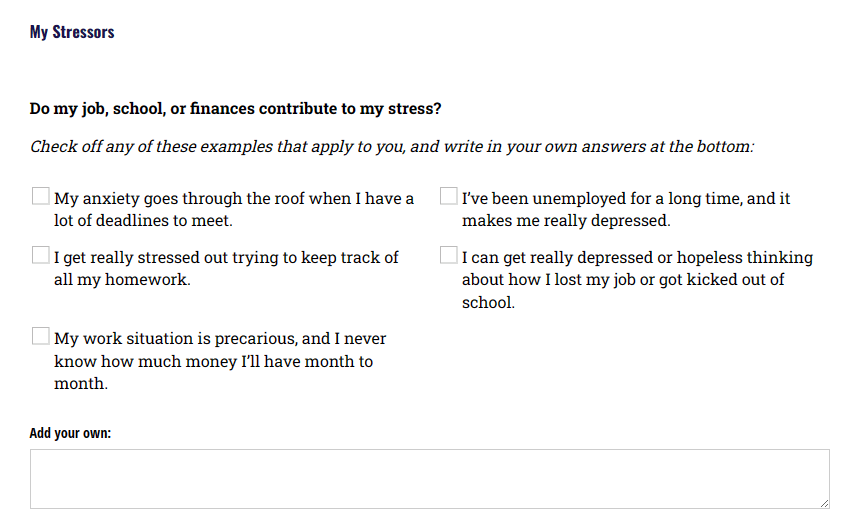

Section 4: Slipping off the tracks

The point of this section is to map out what is hard for us, what we struggle with, and help us develop the self-knowledge to be able to figure out what to do about it. This section is often the hardest one to fill out because it asks us to think about hard times, but the information we gather is really useful in our journey. Often unresolved things from our past can make us feel unsafe or upset in the present – this is called getting triggered. Sometimes our triggers contain useful information about what needs to heal in us, and what we need to express. If you find yourself getting triggered or overwhelmed as you complete your map, take a break and do one of the practices in your wellness toolkit. It can also help to do the T-MAPs process with other people and realize you are not alone.

My answers

Add your own:

My stressors relate to conflicts that arise from my spiritual guidance and trying to get Quakers and/or others to understand that guidance and follow it with me. Or for certain guidance, finding out how to implement it, and then do it myself.

I realize this isn’t much compared to the awful things many people have gone, are going through.

Section 5: Support

One of the main benefits of making an T-MAPs document is being able to get clarity on the things that are important to us and being able to share it with other people. In this section, we identify the people, services, and resources that are the most important sources of support for us. This helps us remember where we can turn when things get hard, and who to stay in touch with along the way

My answers

In this section, we are asked questions about who our support people and networks are.